NG de Bruijn and AUTOMATH

[logic NG de Bruijn AUTOMATH NG de Bruijn visited Caltech in the spring of 1977 to deliver a course on his AUTOMATH mathematical language. I was lucky enough to attend and to have private discussions with him.

AUTOMATH embodies his personal philosophy of mathematics and in particular his view that mathematical objects are essentially typed. In the AUTOMATH languages (they evolved over time) you can introduce types and elements of types. Each element has a unique type. You can also introduce new propositional symbols and instances of them. Introduced elements of a type are constants or parameters while those of a propositional symbol are axioms or assumptions. The parallel treatment of types and propositions makes AUTOMATH the first implemention of the idea of propositions as types. Yet it is much simpler and (by design) weaker than subsequent type theories, with their $\Pi$ and $\Sigma$ type constructors and their internal programming languages. De Bruijn referred to AUTOMATH as a “λ-typed λ-calculus” because it only had one kind of binder, which operated at the level of objects, types and propositions.

AUTOMATH Syntax

The syntax of AUTOMATH looks unappealing now, but it seemed natural in the era of punched cards. The syntax is line based, with three kinds of lines:

- EB lines (empty block openers), introducing a new typed variable––representing a parameter or assumption––to the current context

- PN lines, asserting axiomatically the existence of some primitive notion: a constant or axiom

- Abbreviation lines, which define an identifier as equal to some given expression. Such lines express constructions. They can express the proof of a theorem, coded as its type.

Expressions in AUTOMATH belong to one of three possible levels:

TYPEandPROP(which at first were treated identically)- types and propositions (elements of 1-expressions)

- elements of types or propositions (elements of 2-expressions)

Unlike modern λ-calculi, AUTOMATH does not have nested bound variable scopes enclosed in parentheses. You create a new scope by declaring a variable and its type in an EB line.

* 𝛼 := –– type

Because this is an EB line, 𝛼 can be abstracted over later to create a λ-type. Using PN instead here would introduce type 𝛼 effectively as a constant.

Any time later, an EB line can quote the same variable and then declare a new one, thereby extending the previously named scope.

Here, x will have type 𝛼.

𝛼 * x := –– 𝛼

Because of this odd approach, several scopes can be available at the same time and it’s not so easy to figure out which variables are currently in scope: you have to trace back the chain of variables. A PN or abbreviation line also quotes a variable, designating the corresponding scope. Here, AX is in the scope of both 𝛼 and x.

x * AX := –– finite(x)

The ability to partly back out of a scope allows for some cryptic partial application tricks.

Example: A Definition of Equality

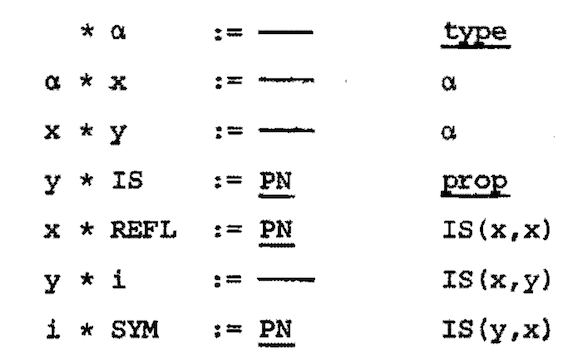

The following bit of code defines the equality relation, IS(x,y).

In AUTOMATH jargon, this is book equality, that is, axiomatically defined mathematical equality, as opposed to the built-in equality by reduction that is intrinsic to AUTOMATH itself. This distinction between book and definitional equality is common to most type theoretic formalisms.

A series of EB lines introduces the type α, then extends that scope with x and again with y, both of type α. Then a PN line introduces the predicate IS, which depends on all three. Note that EB lines can be used to specify the parameters of a primitive notion such as IS.

The next PN line drops y from the scope and introduces the axiom REFL, for reflexivity, of type IS(x,x). The symmetry property will be a rule of inference mapping IS(x,y) to IS(y,x). So now the scope ending with y is extended with i, of type IS(x,y). The symmetry axiom is introduced as the primitive notion SYM, depending on all four variables and having type IS(y,x).

A landmark work was LS van Benthem Jutting’s translation of Landau’s textbook Foundations of Analysis. He demonstrated that substantial mathematical material, including equivalence classes and Dedekind cuts, could be formalised in AUTOMATH––and with more elegance and less effort than could be imagined in the formalism of Principia Mathematica.

Jutting’s work also led to the idea of the de Bruijn factor: the ratio between the size of the formalisation and the size of the original text. That we speak of a factor embodies de Bruijn’s observation that this ratio remained constant as the material being formalised grew more advanced. Sadly, little mathematical material is as carefully written and detailed as Landau’s book.

It’s truly astonishing what the AUTOMATH community was able to accomplish using the tools of the 1970s.

Additional remarks (added later)

-

Geuvers and Nederpelt have recently written a much longer overview of AUTOMATH, set in the context of modern-day type theories.]

-

Wiedijk describes a new implementation, also discussing the relationships among auto and modern proof assistants such as Coq and Agda.