A few small formalisation challenges

[general examples NG de Bruijn John Littlewood Novices getting to grips with interactive theorem proving need examples to formalise. When Russell O’Connor was getting to grips with Coq, he thought that a nice little exercise would be to formalise Gödel’s incompleteness theorem. I hope he will not be offended if I remark that that was a crazy idea, even though he was successful. Below, I list a few proofs that I would like to see formalised. I am not sure how easy they are, but all of them are easier than Gödel’s Theorem!

Filling boxes with bricks

NG de Bruijn published a note that began by pointing out that the dimensions of a brick are typically 1×2×4 and that, although such bricks can be fitted together in numerous ways, it is impossible to fill a volume by such bricks unless it can be done trivially, with all the bricks neatly lined up in rows. He generalises this fact to an arbitrary number of dimensions and he defines necessary and sufficient conditions on the dimensions of bricks for this condition to hold (it does not hold for 1×2×3 bricks). His paper concludes

The questions of the bricks 1×2×4 arose from a remark by the proposer’s son F. W. de Bruijn who discovered, at the age of 7, that he was unable to fill his 6×6×6 box by bricks 1×2×4.

Shockingly, de Bruijn never received a Fields Medal for this work. I’ve had the paper sitting on my computer for 20 years now and never got around to formalising it.

Defining reals without the use of rationals

This is another paper by de Bruijn (I’m clearly a fan of his) and the title is self-explanatory. Can we construct the real numbers in fewer stages than is usual, and in particular, avoiding any quotient constructions? (His approach may appeal particularly to users of type theory systems.) Unfortunately, defining multiplication looks difficult and he doesn’t cover it. Instead he recommends another paper, The real numbers as a wreath product by Faltin et al., which requires the dreaded equivalence classes and might be just the thing for Isabelle/HOL. I know that we have two formalisations of the reals already, but who’s counting?

A simple proof that π is irrational

We know that π is irrational (indeed, transcendental) by the Hermite–Lindemann–Weierstraß transcendence theorem, which has been formalised in Isabelle by Manuel Eberl. But do you really want to rely on some overblown 19th-century result when a cute one page proof is available? The proof involves assuming the contrary, defining some polynomials, taking an integral and eventually obtaining an integer between 0 and 1. This sounds like the same technique used to prove that exponentials were irrational in my earlier post.

Note added 2024-09-13: this challenge has now been fulfilled, by Manuel himself!

Impossibility of cubing the cube

Littlewood, in his Mathematician’s Miscellany, posed the question

Dissection of squares and cubes into squares and cubes, finite in number and all unequal.

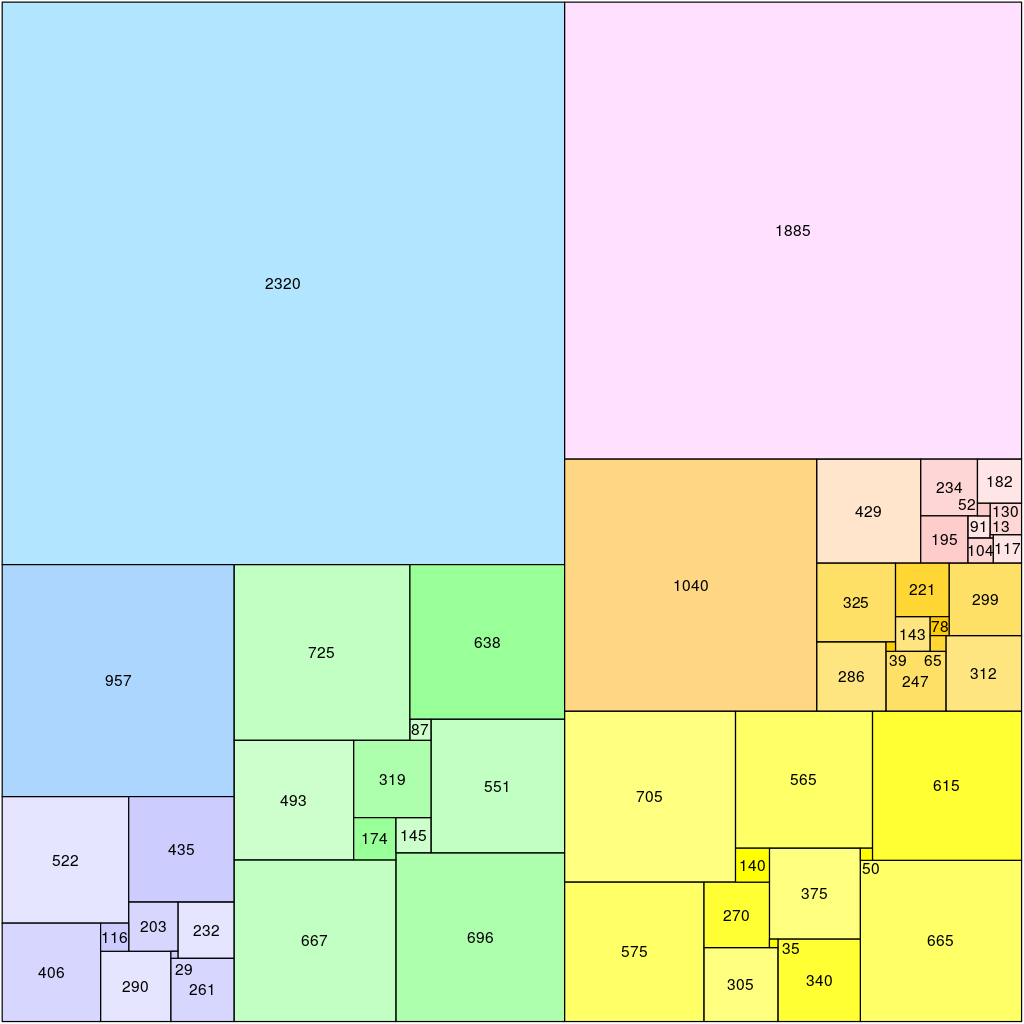

“Squaring the square” turns out to be difficult. The following is the simplest example.

The analogous cube dissection is impossible. Here is Littlewood:

In a square dissection the smallest square is not at an edge (for obvious reasons). Suppose now a cube dissection does exist. The cubes standing on the bottom face induce a square dissection of that face, and the smallest of the cubes at the face stands on an internal square. The top face of this cube is enclosed by walls; cubes must stand on this top face; take the smallest—the process continues indefinitely.”

This is not much of a proof. Floris van Doorn managed to formalise it within 24 hours, in Lean. An Isabelle version is still lacking.

This problem is of interest because it belongs to the famous list of 100 “top” theorems, maintained by Freek Wiedijk. As of today, 98 of them have been proved in at least one system. Isabelle and HOL Light are tied at the top, with 86 problems each.

Mathematics textbooks

I’m sorry to have to mention that the proofs found in mathematics textbooks are frequently little more than a succession of hints and not suitable for formalisation, especially by a novice. However, the wonderful Proofs from THE BOOK is full of nice examples, not too complicated, and with reasonably detailed proofs. You don’t have to understand homological algebra or K-theory. There are still gaps however, so you will have work to do!