The λ-calculus, 2: the Church-Rosser theorem

[general lambda calculus A well-known technique to speed up computer code is to re-order some steps, for example to lift a costly operation out of a loop. In logic, when we can choose what inference to do next, making the right choices yields an exponentially shorter proof. Also in the λ-calculus we sometimes have a choice of reduction steps: the possible outcomes include, at one extreme, terminating exponentially faster or at the opposite extreme, not terminating at all. But it would certainly be vexing if two terminating computations could return different final values. Church and Rosser proved that couldn’t happen, implying the consistency of the λ-calculus and giving us some of the tools needed to study this question in other situations.

Final values in the λ-calculus

As mentioned last time, basic things like numbers and lists are not built into the λ-calculus, but can be encoded. We’ll look at these ingenious encodings in a later post. But here is a teaser: it’s conventional to represent true and false by $\lambda x y.x$ and $\lambda xy.y$, respectively. The latter term also represents zero.

Note that no reductions can be applied to either of these: they are in normal form. (Remember, a reduction is a β or η step; the α-conversions, which just rename bound variables, do not count.) If $M$ is in normal form, then we regard it as a value rather than as a computation. Conversely, if it is not in normal form then further reductions are possible. There exist more nuanced notions of value that make sense of some infinite computations.

If we define \(\let\red=\rightarrow \let\redd=\twoheadrightarrow \newcommand\K{\mathbf{K}} \K\equiv\lambda x y.x\) and \(\Omega\equiv(\lambda x.xx)(\lambda x.xx)\) then $\K M N \redd M$ and $\Omega\red\Omega$. Note that $\redd$ allows zero or many reduction steps. Now the term $\K x \Omega$ can be reduced in various ways, including $\K x \Omega \redd x$ and $\K x \Omega\red\K x \Omega$. The latter reduction can be continued indefinitely, or terminated at any point using the former reduction to yield simply $x$.

And a pro tip: if you intend to do λ-calculus derivations, I strongly recommend using abbreviations, like here. Working out λ-terms in full, you are bound to go wrong.

Equality in the λ-calculus

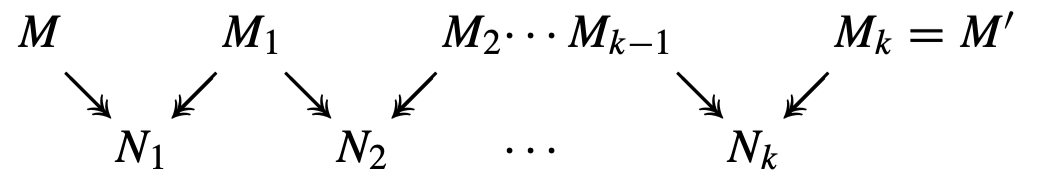

As remarked last time, $M=M’$ means it is possible to transform $M$ into $M’$ through any series of α, β or η steps, possibly within a term and possibly backwards (expansions, as opposed to reductions). So we have the following picture:

From the picture alone, it should be easy to see that equality satisfies many of the basic properties we expect, such as being reflexive, symmetric and transitive. But how can we show that some things are not equal: for example, that $\lambda x y.x \not= \lambda xy.y$?

The Church-Rosser Theorem

The theorem states that if two terms are equal then they can be made identical by a series of reductions. More formally, if $M=N$ then $M\redd L$ and $N\redd L$ for some $L$.

If you really want the gory details of the proof, see the paper by Rosser cited last time. Many early proofs were wrong, tripping up over substitution and free/bound variable clashes. But let’s forget the proof for a moment and first look at some of the consequences.

- If $M=N$ and $N$ is in normal form, then $M\redd N$: reductions alone are enough to reach that normal form.

- If $M$ and $N$ are distinct terms in normal form, then $M\not=N$. For example, $\lambda xy.x\not=\lambda xy.y$.

The latter point above implies the consistency of the λ-calculus and gives us a simple way to recognise when two final values are equal. (Of course, “distinct” ignores irrelevant differences in bound variable names.)

The Diamond Property

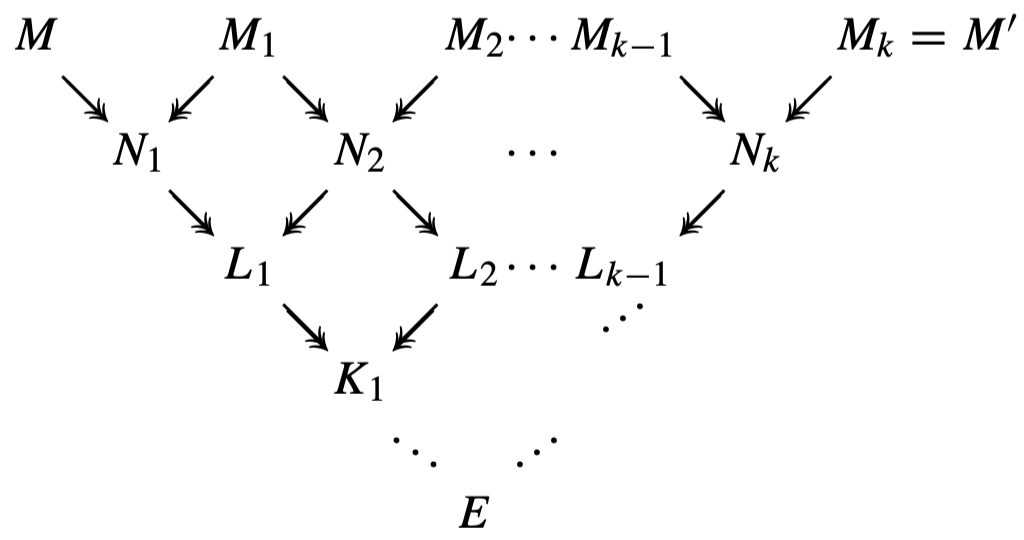

The diamond property states that if $M\redd M_1$ and $M\redd M_2$ then $M_1\redd L$ and $M_2\redd L$ for some $L$: that no matter how far we go reducing a term along two different paths, further reductions can bring them back together. It implies the Church-Rosser Theorem by an obvious tiling argument:

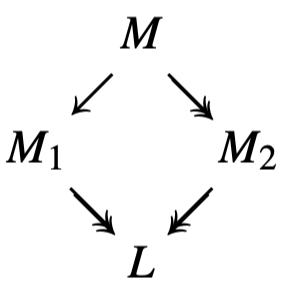

Note that the diamond property can fail for single-step reductions: if $M\red M_1$ and $M\red M_2$ we can’t guarantee that $M_1\red L$ and $M_2\red L$, since multiple steps may be necessary to bring $M_1$ and $M_2$ back together again. But we can prove diamonds of the following sort, setting one reduction on the left against possibly many on the right:

Having established this lemma, a further tiling argument gives us the diamond property in its original form. The proof is a tedious case analysis, and the worst cases involve overlaps: when one reduction duplicates a term containing other possible reductions.

Offshoots of this work include the study of term rewriting systems and their confluence.