ALEXANDRIA: Large-Scale Formal Proof for the Working Mathematician

[general ALEXANDRIA Isabelle Archive of Formal Proofs Mizar HOL system HOL Light Coq ALEXANDRIA is an ERC Advanced Grant with the aim of making verification technology — originally designed to verify computer systems — useful in the practice of professional mathematics. Another project with similar aims has developed around Lean, a proof assistant based on essentially the same type theory as Coq. Without doubt the idea of doing mathematics by machine is in the air. But why?

Mathematicians are fallible

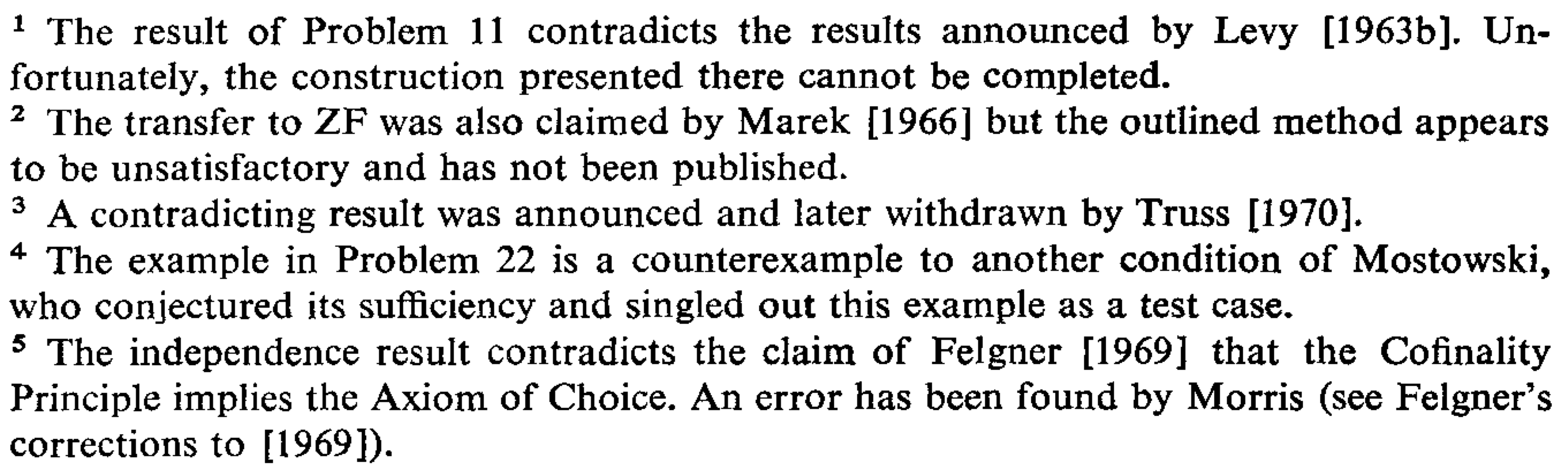

Let me begin by referencing my own proposal for ALEXANDRIA. Simply look at the footnotes of Thomas J. Jech’s monograph, The Axiom of Choice (North-Holland, 1973), at the bottom of page 118:

Let’s just say that this list of doubtful outcomes doesn’t inspire confidence. However, it was the outspoken concerns of the late Vladimir Voevodsky, a Fields medallist, that really pushed the question of mathematicians’ errors out into the open. Anthony Bordg has described the situation in an article, A Replication Crisis in Mathematics?, that has recently been published in the Mathematical Intelligencer. (Full disclosure: Anthony works for ALEXANDRIA.)

By no means all mathematicians share these concerns. One remarkable thing I’ve noticed: the theorem statement tends to be correct (with the possible exception of degenerate cases) even when the proof is a mess. Mathematicians seem to have a deep understanding of the phenomena they work with, even if they don’t always express their arguments accurately. (For now I will forgo detailing my own struggles with careless proofs, while declaring publicly that Jean Larson is not guilty of this.)

A brief history of formalised mathematics

Most of today’s proof assistants were created in the 1980s. The first public release of Isabelle took place in 1986, around the same time as Mike Gordon’s HOL system and the first version of the Calculus of Constructions, which later turned into Coq.

Of these early systems, HOL was the most practical from the start, having been built with the aim of verifying computer hardware. It was immediately put to use verifying significant chip designs. However, this early work required almost nothing that could be called mathematics. None of these early systems even had negative integers.

The impetus for the formalisation of mathematics in the HOL world was the 1994 floating point division bug that forced Intel to recall millions of Pentium chips. John Harrison, a student of Mike Gordon, decided to focus his research on the verification of floating point hardware. John formalised the real numbers and the elements of basic analysis. He also built his own version of the HOL system: HOL Light. Another student of Mike’s, Joe Hurd, decided to verify probabilistic algorithms. To make that possible, Joe formalised measure and probability theory. John went on to formalise a substantial amount multivariate analysis and prove a number of well-known theorems from a famous list. In the years after 2010, especially when I found myself without grant money, I devoted my time to stealing great chunks of the HOL Light library for Isabelle/HOL.

As you may recall from an earlier post, AUTOMATH was developed specifically to formalise mathematics, starting in the 1960s. Another impressive effort in the formalisation of mathematics was the Mizar project, which started in 1973. Unfortunately, people in the West tended to overlook scientific developments in Eastern Europe and Mizar did not get the attention it deserved until the 1990s. Mizar introduced a structured language for expressing mathematical arguments, which was the inspiration for Isabelle’s Isar language. Mizar also had an ingenious language for expressing and combining mathematical properties, e.g. finite abelian group, which still seems to be unmatched by any other system.

One event that did attract widespread attention was Georges Gonthier’s formalisation of the four colour theorem in Coq. The original proof of this theorem by Appel and Haken was widely disliked, depending as it did upon hundreds of pages of hand calculations and a computer program written in assembly language to check billions of cases. Georges used Coq’s internal programming language to run those checks in a fully verified environment. A cynic could argue that this is merely replaced the need to trust one computer program by the need to trust another one, but for most people it settled the question. Georges went on to lead a much larger project, to formalise the odd order theorem, a major result about finite groups, formalising a proof that was hundreds of pages long. Another notable formalisation confirmed Thomas Hales’s proof of the Kepler conjecture, which concerned the densest possible packing of spheres. Like the four colour proof, the issue of concern was the reliance on a computer program to check a large number of cases.

Pushback against earlier formalisations

As mathematicians started to become attracted to this area, they started to raise criticisms of the sort of work described above. A hint of their objections can be seen in the abstract of the paper “Formalising perfectoid spaces” by Kevin Buzzard et al. (Italics mine.)

Perfectoid spaces are sophisticated objects in arithmetic geometry introduced by Peter Scholze in 2012. We formalised enough definitions and theorems in topology, algebra and geometry to define perfectoid spaces in the Lean theorem prover. This experiment confirms that a proof assistant can handle complexity in that direction, which is rather different from formalising a long proof about simple objects.

The complaint is that the previous examples, despite comprising hundreds of thousands of lines of formal text covering many areas of mathematics, did not come close to matching the complexity of mathematics as it is practised today. Note that the objective of the experiment here was not to prove anything but merely to define particular sophisticated objects.

A specific criticism can be directed at the HOL Light formalisations and the related ones in Isabelle/HOL: they are not formalised in a general, scalable manner. John Harrison was interested in the special case of Euclidean spaces, $\mathbb{R}^n$. He wanted the type system to do as much work as possible, so he found an ingenious way to encode $\mathbb{R}^n$ as a type even though the HOL Light type system did not admit types with integer parameters such as $n$. Type parameters were allowed, so Harrison decided to encode $n$ as an $n$-element type. In this manner he was able to formalise a great many theorems. As these developments became more sophisticated, the ability to treat $\mathbb{R}^n$ so cleverly became a limitation, as many of them held much more generally.

The Isabelle/HOL equivalents of those proofs were based on axiomatic type classes (more on them another time) so they were quite a bit more general than $\mathbb{R}^n$. But a lot of this generality was illusory. The Isabelle library includes many theorems about topological spaces, for example, but those spaces must be types and there are a great many topological spaces that cannot be formalised as Isabelle types. It’s not actually difficult to formalise topological spaces and similar objects in Isabelle/HOL, but it’s a bit discouraging to think that all of those proofs need to be redone in a more general setting.

Highlights of recent work

One criticism that stung was that previous formalisation efforts had focused on 19th-century mathematics. Can we cope with the demands of mathematics as it is done today? There’s a vast amount of work happening now using Lean, much of it inspired by Kevin Buzzard. Here I would prefer to highlight the work of the Isabelle community. And I’d like to begin with some of the outputs of the ALEXANDRIA project, in no particular order. None of them are 19th-century!

- Szemerédi’s Regularity Lemma, a landmark result concerning the structure of very large graphs

- Irrationality Criteria for Series by Erdős and Straus formalises a paper published in 1974 about certain infinite series

- Combinatorial Design Theory, apparently the first formalisation of block designs, due to Chelsea Edmunds, one of my PhD students

- Grothendieck’s Schemes in Algebraic Geometry answers the challenge set by the Lean community to formalise those objects

The last achievement mentioned above is particularly important, as it refutes the commonly repeated claim that simple type theory (used by Isabelle/HOL) is insufficient to do real-world mathematics. Other notable work (not funded by ALEXANDRIA) includes a formalisation of forcing and a sophisticated algorithm to factor real and complex polynomials with algebraic coefficients. Finally, please allow me to plug my own formalisation of Gödel’s incompleteness theorems, including the only formalisation of the second theorem.

All the material mentioned above has been published in Isabelle’s Archive of Formal Proofs, and I look forward to welcoming your own submission one day.