The de Bruijn criterion vs the LCF architecture

[general Robin Milner MJC Gordon LCF NG de Bruijn Stanford A key objective of formalising mathematics is to ensure its correctness. We have previously considered how we can know whether a given logical formalism is faithful to mathematical reasoning. That raises another question: given the prevalence of errors in computer programs, how can we guarantee that our proof assistants are correct? Two separate approaches are the de Bruijn criterion and the LCF architecture, and I’d like to advocate a third.

The de Bruijn criterion

The de Bruijn criterion involves storing the low-level logical proof in full so that it can be checked later by an independent program. Henk Barendregt and Freek Wiedijk define it as follows:

A verifying program only needs to see whether in the putative proof the small number of logical rules are always observed. Although the proof may have the size of several Megabytes, the verifying program can be small. … If someone does not believe the statement that a proof has been verified, one can do independent checking by a trusted proof-checking program. … A Mathematical Assistant satisfying the possibility of independent checking by a small program is said to satisfy the de Bruijn criterion.1

Here by the way we must distinguish between

- the proof document: the high-level script, written in some tactic language, given to the proof assistant

- the proof object: the low-level formal construction using the rules of the logical calculus

The de Bruijn criterion ignores the tactic high-level script and simply checks that the low-level proof is correct and delivers the claimed result. It is satisfied by type theory proof assistants such as Coq, where proof objects are inherent in their actual proof calculus. Its main selling point is that the checker can be written by somebody who absolutely distrusts the supplied proof. They only need to trust their own system—and the logical calculus itself.

The LCF architecture

The chief drawback of the de Bruijn criterion was already in 1972 a problem with Robin Milner’s proof assistant, Stanford LCF: proof objects easily fill up memory. I am writing on a 32 GB machine while the Stanford AI Lab’s PDP-10 could address little more than 1 MB (and was shared by dozens of researchers). However, our proofs have grown as rapidly as our computers and it is still not difficult to run out of memory.

In developing the successor system, Edinburgh LCF, Milner

had the idea that instead of saving whole proofs, the system should just remember the results of proofs, namely theorems. The steps of a proof would be performed but not recorded, like a mathematics lecturer using a small blackboard who rubs out earlier parts of proofs to make space for later ones. To ensure that theorems could only be created by proof, Milner had the brilliant idea of using an abstract data type whose predefined values were instances of axioms and whose operations were inference rules. Strict typechecking then ensured that the only values that could be created were those that could be obtained from axioms by applying a sequence of inference rules – namely theorems.2

And so, this software architecture ensures that the logical rules of the calculus are always applied correctly. The design is reminiscent of operating systems based on a kernel that has the sole right to perform unsafe operations. However, a sceptic must trust this kernel: the proof assistant does not deliver any sort of certificate that could be checked independently.

The LCF architecture refers to precisely this: a proof assistant that securely encapsulates the rules of the logical calculus within an abstract data type. It must be coded in a strongly typed language providing a suitable notion of abstract type. Confusion about the meaning of “LCF” is widespread because Edinburgh LCF introduced many other features common to modern-day proof assistants, in particular a subgoaling proof style based on backward-chaining reasoning steps and a system of “proof tactics” for accomplishing this. The LCF architecture is an alternative to the de Bruijn criterion, not an implementation of it. The use of abstract types in the LCF architecture has absolutely nothing to do with the well-known propositions-as-types correspondence.

Advocates of the de Bruijn criterion betray a feeling of moral superiority: “so you don’t store proof objects?” (Spoken in a tone of voice suitable for alluding to an abomination.) Seemingly acceptable however are the numerous tricks popular among Coq users to minimise the burden of proof objects.

Why then do we still need a 32 GB machine? Not to store proof objects, but to allow the simultaneous execution of six separate proof engines (in addition to Isabelle itself) to help discover proofs themselves. It also lets us work in theory hierarchies as big as this one or that one.

Further doubts?

Even if the proof has been fully checked, there is still plenty that can go wrong. The most important concern is the correct formulation of the definitions and theorem statements: if they are wrong, the proofs mean nothing. This concern is less relevant to the formalisation of mathematics, where the necessary definitions and assertions are given to us, though ambiguities and errors are still possible. (More on this later!) It is a major concern when a real-world problem is being formalised, because compliance between a formal definition and real-world constraints is inherently imprecise. My personal bugbear is proofs involving computer security, where security models and protocols have often been formalised in a dubious way to favour the desired result (to prove correctness, or often, to “reveal” a spurious attack).

The most extreme doubts arise when actual misconduct is suspected. For example, imagine paying a contractor to deliver a verified operating system. It’s easy to imagine corners being cut in the verification and the crime somehow concealed, perhaps even by tampering with the parsing and display of formulas. Once we go down this route however, it becomes necessary to build your proof assistant using all the techniques of security engineering against some imagined threat model. To my mind this smacks of paranoia, but such attitudes are not hard to find.

What about reading the actual script?

The LCF architecture, like the de Bruijn criterion, ignores the high-level proof altogether. One reason to make our proof scripts as legible as possible is that sceptical readers (especially mathematicians) will want assurances that are completely independent of computers. A kernel architecture using abstract data types will mean nothing to them, and an independent proof checker is still a great heap of computer code. It’s essential that the formal proof itself should be legible, its structure visible and evident, the intermediate assertions plainly written out. A legible proof can even reveal incorrect definitions, since the proof steps won’t follow the expected line of reasoning.

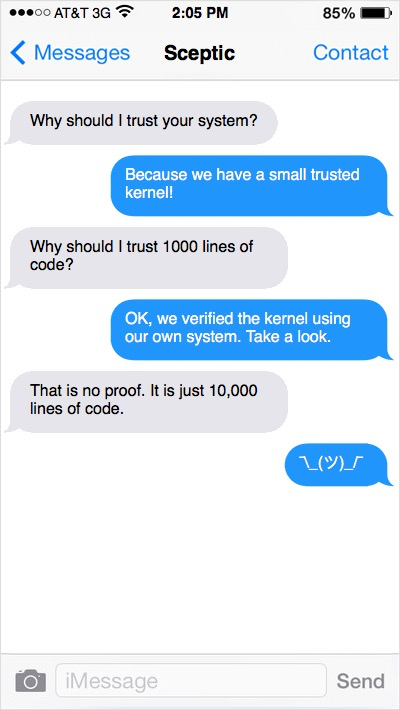

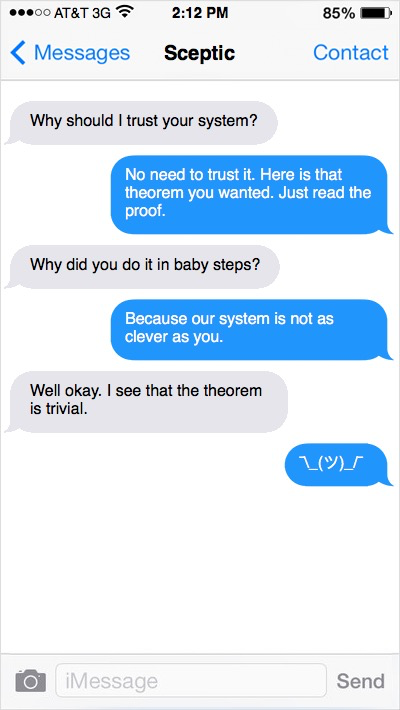

The following two text conversations contrast the two approaches:

*

*

Of course, we want both.

-

H Barendregt and F Wiedijk, in The challenge of computer mathematics (page 2362) ↩

-

MJC Gordon. “From LCF to HOL: a short history”, in Proof, Language, and Interaction: Essays in Honour of Robin Milner, p. 170. Available for free here.) ↩