Mathematical truth, mathematical modelling and axioms

[general logic Imre Lakatos philosophy The recent COVID-19 pandemic has given us a striking demonstration of science in action. Over a period of two years, scientists around the world examined this unknown pathogen. They decoded its genome and developed vaccines and treatments. But some people were not impressed: since scientific advice could change from month to month, scientific truth was fallible. “Sceptics” preferred to rely on treatments advocated by quacks based on feeble evidence but promoted with absolute confidence. Some fell ill but continued to cling to quack advice and conspiracy theories until literally their dying breath. Scientific truth is regularly challenged by new observations. On the other hand, mathematical truth is infallible, right?

Truth in mathematics

For mathematical truth, our starting point must be the classic work Proofs and Refutations: The Logic of Mathematical Discovery by Imre Lakatos. Lakatos tells the story of Euler’s formula, which relates the vertices, edges and faces of polyhedra. He considers a sequence of counterexamples, such as cylinders, polyhedra containing tunnels, and solids consisting of two polyhedra joined at a single vertex or edge.

I can’t agree with Lakatos’ apparent view that mathematical proof and scientific proof amount to the same thing. If they were, we’d have to regard the Riemann Hypothesis as true, as it’s been checked by computer for billions of cases over an extremely wide range. The numerous counterexamples to Euler’s formula represent the vagueness of the word “polyhedron”, and—though I’m no philosopher—cannot be compared with the discovery of a hitherto unknown organism, disease or treatment. Modern geometry can define “polyhedron” precisely, and Euler’s formula has even been generalised beyond the three-dimensional case (apparently with a valid proof). Mathematical truth and scientific truth are fundamentally different.

Mathematical models in science (and in formal verification)

The Earth was believed to be the centre of the Universe until Copernicus proposed his heliocentric model. Placing the Sun at the centre greatly simplified the orbits of the planets compared with the older, Ptolemaic model. But that wasn’t the end: we now know that the Universe is infinitely more complex than Copernicus imagined.

Simple, abstract models are ubiquitous in science. Every student of physics has explored a world where blocks slide down frictionless slopes and spheres trace perfect parabolas with no air resistance. Seemingly unrealistic models are also common in verification. Mike Gordon’s hardware models ignore the quirks of electronics, such as gate delays and fan-outs. Cryptographic protocols are typically verified (alternative link) assuming that encryption is unbreakable. How can we justify such unrealistic assumptions?

- You have to stop somewhere. To capture electronic circuits completely we’d have to descend to the level of electrons and quarks, and even they belong to a model of physics.

- There are multiple perspectives. Gordon’s models deal with one critical issue: the functional correctness of circuits. Other issues (e.g. clock rate) can be dealt with separately.

Similarly, a detailed model of a protocol running on TCP/IP using specific encryption algorithms would be unworkable. A faulty protocol can be defeated without breaking the encryption, e.g. through a man-in-the-middle attack. That a cryptographic protocol is immune to such attacks can be proved separately from lower-level implementation matters.

Both COVID-19 researchers and climate scientists have been attacked for their use of models, but that’s how science is done. Political demands for scientists to do without models are as senseless as demands for a “chemical-free body” or Nadine Dorries asking Microsoft to get rid of algorithms. (Dorries is the UK’s Secretary of State for Digital, Culture, Media and Sport. Not sure about the digital. Or the culture, etc.)

The purpose of a model is to capture just enough detail to cover some perspective of concern. A model is useful if it can make predictions, and we simply need to bear its limitations in mind. For example, if we verify a processor design using Gordon’s techniques, it’s essential not to oversell what has been proved, remaining aware of our model’s limitations. A security protocol can be correct in the abstract but have fatal flaws in an implementation.

Axioms in mathematics

To a mathematician, a model is something else entirely: a construction (typically a set) satisfying a given collection of axioms. In many cases, in apparent inversion of the situation in science, the axioms themselves capture just a few essential aspects of already existing constructions: we had the models before we had the axioms. In a few cases, such as the Zermelo-Fraenkel axioms or the $\lambda$-calculus, the axioms were inspired by other considerations. Without a model or other good reasons, people feel uncomfortable about using such axiom systems.

Dana Scott has written (also here) that the axioms of group theory are a distillation of the properties of the set of permutations on a set, while those of combinatory logic and the $\lambda$-calculus require serious justification. (Which he provided. See my prior post.)

The adoption of particular axioms is not a matter of belief. The Greeks knew that the world was round, but they assumed the parallel postulate, which is false on a sphere. They developed Euclidean Geometry, the geometry of the plane. Presumably they had already adopted the plane as an idealised but natural mathematical model of the surface of the Earth. If we insisted that geometry must capture a spherical Earth, we’d even have to give up infinite lines, and therefore the continuum. Little of what we recognise as mathematics would survive.

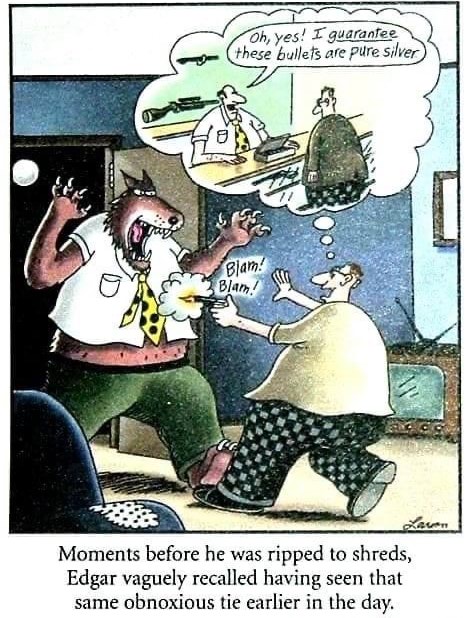

It’s worth remembering that the parallel postulate was seen as controversial for millennia. This gives us a perspective on other controversial axioms, such as the axiom of choice (AC). A constructive colleague once told me “the axiom of choice is a lie”. He’s wrong. This is a lie:

His attitude is almost comprehensible in the case of a confirmed Platonist, for whom axioms are facts about mathematical objects that really exist somewhere out there. However, such an attitude makes no sense for an intuitionist, for whom mathematical objects live only in our minds and nobody gets to dictate what sort of mathematics lives in someone else’s mind.

Axioms are not supposed to assert facts. It’s normal mathematics to explore the consequences of AC on Monday, and those of the axiom of determinacy (which contradicts AC) on Tuesday. As we explore the consequences of different axioms, at issue isn’t whether they are true or even useful: only whether they are interesting.