Revisiting an early critique of formal verification

[verification philosophy formalised mathematics Principia Mathematica In 1979, a paper appeared that challenged the emerging field of program verification: “Social Processes and Proofs of Theorems and Programs”, by Richard DeMillo, Richard Lipton and Alan Perlis (simply the authors, below). They pointed out that proofs in mathematics bore no resemblance to the formalisms being developed to verify computer programs. A mathematical proof, they argued, was an argument intended to persuade other mathematicians. A proof’s acceptance by the mathematical community took place through a social, consensual process and not through some sort of mechanical checking. Proofs of programs were too long, tedious and shallow to be checked through a social process. Some of their points were right, but their main argument was, well, incredibly wrong.

Background

Program verification emerged at the end of the 1960s with the publication of Robert W Floyd’s “Assigning Meanings to Programs” and Tony Hoare’s “An axiomatic basis for computer programming”. In his 1971 “Proof of a Program: FIND”, Hoare worked through the correctness conditions for a subtle algorithm by hand. Automated program verification tools slowly started to appear, such as Gypsy and the Stanford Pascal Verifier (which I have experimented with). These early tools were not very capable and some lacked a sound logical basis. When I was working at the Stanford AI Lab in 1979, the main computer (shared by all faculty and students) had just over one megabyte of memory and we were asked not to overburden it by using the arrow keys when editing. So I’m amused to see the authors complain about “the lack at this late date of even a single verification of a working system”.

Their argument

The authors’ argument rests on two pillars:

- Formal proofs are extremely low-level, “literally unspeakable” and infeasibly long.

- Mathematicians’ traditional method of validating a proof through discussion is the right way to establish the truth of any proposition.

The first pillar rests on their claim that Whitehead and Russell’s Principia Mathematica was a “deathblow” for the idea of formalisation, because it “failed, in three enormous, taxing volumes, to get beyond the elementary facts of arithmetic.” (Indeed, 362 pages were needed to prove 1+1=2.) They also mention a logician’s claim that the formalisation of a certain result by Ramanujan would take 2000 pages “assuming set theory and elementary analysis” and would be of inconceivable length if derived “from first principles”. Not satisfied with this, they speculate that “ordinary, workaday mathematical proofs” would require a computer large enough to “fill the entire observable universe” even assuming “the luxury of a technology that will produce proton-size electronic components connected by infinitely thin wires”.

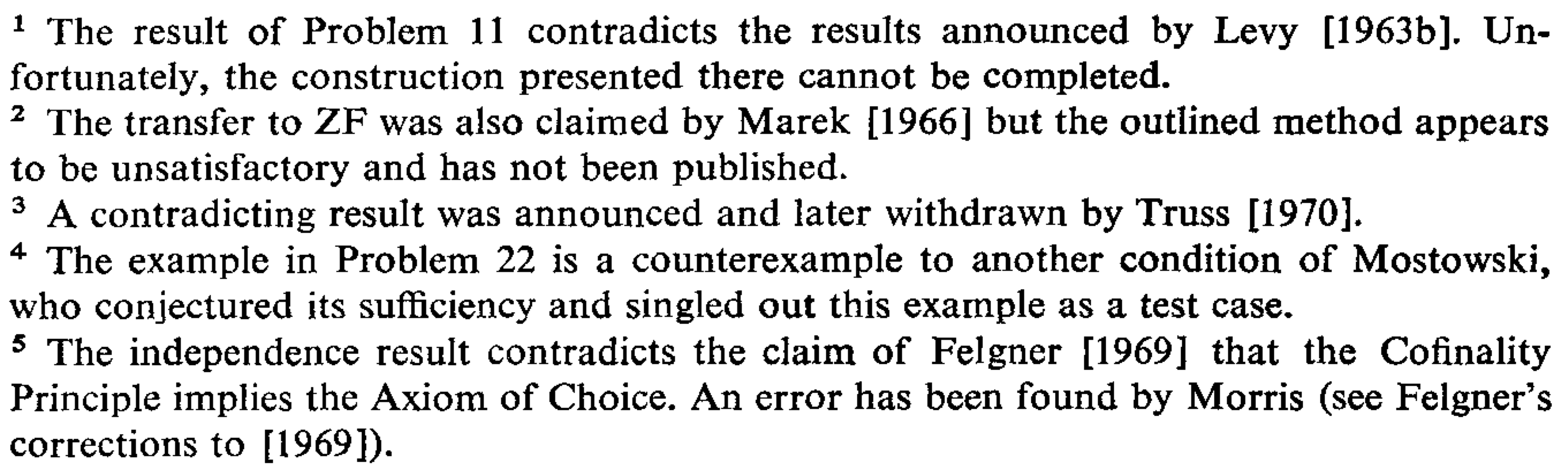

Regarding the second pillar, the authors remark that the vast majority of theorems published by mathematicians are never accepted by the community, being contradicted, thrown into doubt or simply ignored. They proceed to quote verbatim a series of footnotes they found on page 118 of Jech’s monograph on the axiom of choice:1

The authors seem to revel in the fallibility of mathematicians. They continue:

Even simplicity, clarity, and ease provide no guarantee that a proof is correct. The history of attempts to prove the Parallel Postulate is a particularly rich source of lovely, trim proofs that turned out to be false.

They go on to flirt with the idea of abandoning the classical idea of proof altogether in favour of some sort of “probabilistic theorems”.

Their argument, viewed from the 21st century

The pillars of their argument have not stood the test of time. Within a few years of publication, researchers were proving significant mathematical results using proof assistants that reduced reasoning to “first principles”: Wilson’s theorem and the Church-Rosser theorem were both proved in 1985; Gödel’s incompleteness theorem followed in 1986 and Quadratic Reciprocity in 1990. All of this work was done using Nqthm, more popularly known as the Boyer–Moore theorem prover. By 1994, enough mathematics had been formalised for Robert Boyer to propose the QED project: to build a machine-checked encyclopedia of mathematics. Today, a vast amount of mathematics has been formalised – in Isabelle, Lean, Rocq and other systems – including one of Ramanujan’s theorems, (proved in 20 pages, not 2000). The challenge of formalising the “100 famous theorems” has been met – except for Fermat’s last theorem, and Kevin Buzzard is working on that.

The situation regarding the second pillar is more interesting. A paper published in 2014 would seem at first sight to buttress the authors’ arguments, providing many further examples of errors in mathematics papers being corrected by the community:

I was giving a series of lectures, and Pierre Deligne (Professor in the School of Mathematics) was taking notes and checking every step of my arguments. Only then did I discover that the proof of a key lemma in my paper contained a mistake and that the lemma, as stated, could not be salvaged. Fortunately, I was able to prove a weaker and more complicated lemma, which turned out to be sufficient for all applications. A corrected sequence of arguments was published in 2006.

However, Voevodsky’s attitude to mathematical mistakes turned out to be very different from the authors:

This story got me scared. Starting from 1993, multiple groups of mathematicians studied my paper at seminars and used it in their work and none of them noticed the mistake. And it clearly was not an accident. A technical argument by a trusted author, which is hard to check and looks similar to arguments known to be correct, is hardly ever checked in detail.

And this is why the Isaac Newton Institute for mathematical sciences devoted the summer of 2017 to a workshop programme entitled Big Proof. Aimed at “the challenges of bringing [formal] proof technology into mainstream mathematical practice”, it was attended by a great many mathematicians. Recently, Fields medallist Peter Scholze asked the verification community to confirm a key lemma of his prior to its publication. It was completed in 18 months.

Verifying computer systems

Although the authors’ arguments are founded on proofs in mathematics and the alleged limitations of formal logic, we also need to talk about the point of all this, namely program verification. The authors are correct that real programs can be millions of lines long, with messy and complicated specifications. We are never going to see a verified Microsoft Word. Nevertheless, a number of substantial, useful programs have been formally verified, such as the seL4 secure operating system kernel and the CakeML verifiably bootstrapped compiler.

Hardware verification was not on the authors’ radar in 1979, but it has been even more successful. Michael Gordon and his team proved the correctness of a simple minicomputer in 1983, of a network interface chip in 1985, and of a commercial, military grade microprocessor in 1988. Software verification turned out to be a tougher challenge, but 1989 saw a proof of a code generator for a subset of the Gypsy language.

Today, verification techniques are embedded in the development process of companies like Nvidia and Intel. The old assumption that verification was only affordable for safety critical applications was exploded 30 years ago, with the Pentium 5 division bug. Nobody likes to lose half a billion dollars. These days, any mission-critical software or hardware is a candidate for verification.

And they cope with the frequent modifications that are inherent in all system development:

There is no reason to believe that verifying a modified program is any easier than verifying the original the first time around.

You just have to tweak the proof you have already.

What was the point?

I have struggled to understand what motivated the authors to write such a vitriolic polemic in the first place. Here is a brief extract from the paper’s two pages of conclusions:

The concept of verifiable software has been with us too long to be easily displaced. For the practice of programming, however, verifiability must not be allowed to overshadow reliability. Scientists should not confuse mathematical models with reality–and verification is nothing but a model of believability. Verifiability is not and cannot be a dominating concern in software design.

Were we living on the same planet? Although the 1970s did see attempts to promote high-level languages – Alphard, CLU, Euclid – they went nowhere. Unsafe languages such as BLISS, BCPL and C rapidly took over. The UNIX operating system (coded in C) was announced in 1971. The hugely influential Xerox Alto workstation (coded in BCPL) appeared slightly later.

As for program verification tools, I have wracked my brain and consulted contemporary literature, coming up with only this (by 1979):

- a PhD thesis from Carnegie Mellon University

- Donald Good’s group at Austin (the Gypsy verification system)

- David Luckham’s group at Stanford (the Stanford Pascal verifier)

- Robert Constable’s group at Cornell (PL/CV)

Robert Boyer and J Moore’s work on program verification lay in the future. Other work on automatic theorem proving and logic programming was focused on AI, not verification. Where was the dragon that they were so desperate to slay?

What they got right

Credit must be given where due. The authors did make a couple of extremely important points, which continue to be overlooked to this day.

Since the requirement for a program is informal and the program is formal, there must be a transition, and the transition itself must necessarily be informal.

Even with a perfect verification tool, it is essential to take responsibility for your formal specifications. This is often easy, since today we typically verify some sort of component (say, a secure enclave) whose natural specification is already mathematical. Nobody can prove that a car’s electronic control panel is ergonomic, but formal tools are used to ensure that it behaves correctly.

A good proof is one that makes us wiser.

The paper repeatedly emphasises attributes of good proofs such as simplicity and clarity. They stress the crucial role of intuition in understanding mathematical concepts. This is absolutely right. Regular readers of this blog will have seen the many examples where I walk through Isabelle proofs step-by-step. Perfectly readable they are not – they are code – but with practice they are understandable. They are understandable enough that people clip out chunks of proofs to adapt for use elsewhere, which is analogous to how mathematicians borrow from one another.

It seems to us that the scenario envisioned by the proponents of verification goes something like this: The programmer inserts his 300-line input/output package into the verifier. Several hours later, he returns. There is his 20,000-line verification and the message “VERIFIED.”

Although this is another straw man, many people claim to have verified something, offering as evidence a formal proof using their favourite tool that cannot be checked except by running that very tool again, or possibly some other automatic tool. A legible formal proof allows a human reader to check and understand the reasoning. We must insist on this.

Coda

I owe the authors a debt of gratitude for finding that page in Jech’s The Axiom of Choice listing all those errors. I included the exact same page in my successful grant proposal for verifying mathematics. Although I had stumbled across it elsewhere, they are surely the original source.

The authors’ attitude to mathematical errors reminds me of anti-vaxxers who say “getting measles and mumps is simply a part of childhood”. It was, and children died. Let’s do something about it.

-

T J Jech, The Axiom of Choice (North-Holland, 1973). ↩