Broken proofs and broken provers

[general verification Isabelle memories People expect perfection. Consider the reaction when someone who has been vaccinated against a particular disease nevertheless dies of it. Mathematical proof carries the aura of perfection, but again people’s expectations will sometimes be dashed. As outlined in an earlier post, the verification of a real world system is never finished. We can seldom capture 100% of reality, so failure remains possible. Even in a purely mathematical proof, there are plenty of ways to screw up. Plus, proof assistants have bugs.

Some badly broken proofs

Many years ago, I refereed a paper about the verification of some obscure application. I recall that the theoretical framework depended on several parameters, among them $z$, a nonzero complex number. This context was repeated for all the theorems in the paper: each included the assumption $\forall z.\, z\not=0$. Needless to say, that assumption is flatly false. The author of the paper had presumably intended to write something like $\forall z.\, z\not=0 \to \cdots$. The error is easy to overlook, and I only became suspicious because the proofs looked too simple. The entire development was invalid.

Isabelle would have helped here.

For one thing, Sledgehammer warns you if it detects a contradiction

in your background theory.

And also, when you have a series of theorems that all depend on the same context,

you can prove them within a locale, with assumptions such as $z\not=0$ laid out clearly.

Even without locales, the Isabelle practice of listing the assumptions

separately in the theorem statement would have avoided the problem.

Isabelle newbies frequently ask why we prefer inference rules with explicit premises and conclusions over formulas like $\forall x.\,P(x) \to Q(x)$.

It is to avoid the confusing clutter of quantifiers and implications and

the further clutter of the proof steps needed to get rid of them

(intros in Rocq).

But in some cases, Isabelle itself can be the problem. Once, a student had proved some false statement and then used it to prove all the other claims (easily!). But how did he prove the false statement in the first place? Actually he didn’t: his proof was stuck in a loop. By a quirk of multithreading: when processing a theory file, If one Isabelle thread gets bogged down, other threads will still race ahead under the assumption that the bogged-down proof will eventually succeed. Such issues are easily identified if you run your theory in batch mode: it would simply time out. I have given an example of this error in another post. Experienced users know to be wary when proofs go through too easily.

Another way to prove nonsense is getting your definitions wrong. With luck, the lemmas that you have to prove about your definitions will reveal any errors. Apart from that, you will be okay provided the definitions do not appear in the main theorem. Recently I completed a large proof where I was deeply unsure that I understood the subject matter. Fortunately, the headline result included none of the intricate definitions involved in the work. The key point is that making a definition in a proof assistant does not compromise its consistency. If the definition is wrong, theorems mentioning it will not mean what you think they mean, but you will not be able to prove $1=0$.

This is also the answer to those who complain that $x/0=0$ in Isabelle (also, in HOL and Lean): if your theorem does not mention the division symbol then it doesn’t matter. And if it does mention division, then the only possible discrepancy between Isabelle’s interpretation and the traditional one involves division by zero; in that case, there is no traditional interpretation to disagree with.

Soundness bugs in proof assistants

We expect proof assistants to be correct, but how trustworthy are they really? I spent a little time tracking down soundness errors in a few of them: first, naturally, Isabelle, where there has been one error every 10 years.

In 2025 (last February), somebody showed how to prove false in Isabelle/HOL using normalisation by evaluation, which bypasses the proof kernel. This was not a kernel bug, and unlikely to bump into by accident, but it was obviously unacceptable and was fixed in the following Isabelle release.

In 2015, Ondřej Kunčar found a bug in Isabelle/HOL’s treatment of overloaded definitions. A particularly cunning circular definition was accepted and could be used to prove false. I recall arguing that this was not really a soundness bug. But just above, I have noted how important it is that definitions preserve consistency: in particular, that they can be eliminated (in principle) by substitution. Kunčar and Popescu put a great effort into not just fixing this bug but putting the definition mechanism onto a sound theoretical bases.

In 2005, Obua discovered that essentially no checks were being performed on overloaded definitions. He discovered a not-quite-so cunning circular definition that could be used to prove false (details in the previous paper).

There must have been earlier soundness bugs in Isabelle, but I cannot remember any beyond those above. Definitions were not being checked for circularity because Isabelle was specialised research software and I couldn’t be bothered to stop people from hanging themselves: that old UNIX spirit. But good computer systems do protect users.

An early soundness bug in HOL88 also involved definitions. It was omitting to check that all the variables on the right hand side of the definition also appeared on the left-hand side. That leads to a contradiction trivially. A subtler error is to allow a definition where the right hand side is “more polymorphic” than the left and depends on some property of a type.

I can still remember a soundness bug that I introduced into LCF 40 years ago. I was coding 𝛼-conversion: a function to test whether two λ-expressions were equivalent up to renaming of bound variables. For example, $\lambda x.x$ and $\lambda y.y$ are 𝛼-equivalent. But I was coding in LISP and used a popular optimisation of testing for pointer equality, overlooking that it made no sense here. My code regarded $\lambda x.x$ and $\lambda y.x$ as equivalent. This sort of bug is particularly dangerous because it is in the kernel.

I have never heard of any soundness bug in Rocq, but fortunately, the Rocq team maintain a convenient list of critical bugs. It’s scary, and you have to wonder what they did wrong. After all, Lean is based on a similar calculus and seems to have a good soundness record. Another seriously buggy proof assistant is PVS; at least, it was 30 years ago. PVS has no proof kernel.

My impression is that the LCF style systems, including the HOL family as well as Isabelle, have an excellent record for soundness, confirming Robin Milner’s conception from half a century ago – and with no countervailing penalty.

So can we rely on machine proofs?

Of the woeful tales related above, I am not aware of any that had practical implications. Even soundness bugs seem to have a limited impact. Griffioen and Huisman wrote of PVS

The obvious question thus arises, why use a proof tool that probably contains soundness bugs? … PVS is still a very critical reader of proofs.

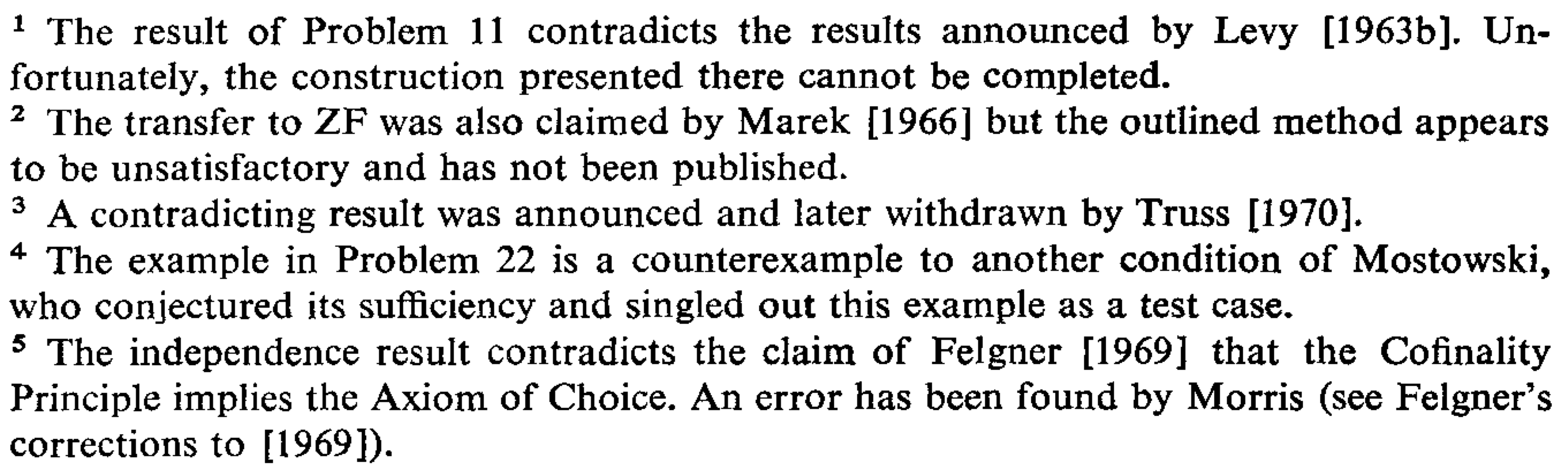

A close examination of almost any proof published in a mathematics journal will identify errors. Most are easy to fix, but the persistence of errors must undermine our confidence in published mathematics. Let’s recall once again that remarkable group of footnotes from The Axiom of Choice, by T J Jech:

This exact list was used by DeMillo et al. as evidence for the strength of the mathematical community and decades later, in my own grant proposal, as evidence for its weakness. In the case of machine proofs, with the crucial caveat that abstract models of the real world often turn out to be inadequate, we do not find errors. Evidence from testing suggests that verification works.

In my corner of the world of interactive theorem proving, we take soundness seriously. Mike Gordon strongly promoted a definitional approach: no axioms ever, all proof developments built upon pure higher-logic from definitions alone, to avoid any danger of inconsistency. Many of the variants of the HOL system owe their existence to a desire for ever greater rigour. For example, John Harrison writes “HOL Light is distinguished by its clean and simple design and extremely small logical kernel.” The HOL light kernel was later verified. The apotheosis of this project is the Candle theorem prover, created by porting HOL Light to the CakeML language. Candle has been proved to correctly implement higher-order logic, and moreover, this theorem has been established for its compiled machine code. We have no way of knowing whether higher-order logic is consistent, but if it isn’t, there will be nothing left of mathematics.

Incidentally, higher-order logic is remarkably self-contained. Over past decades, the HOL provers and Isabelle/HOL have gained numerous extensions: recursive datatypes, general recursive function definitions with pattern matching, inductive definitions and coinductive definitions. These are all definable within higher order logic, whereas similar capabilities in dependent type theories always seem to require extensions to the kernel. And that means, any bugs are kernel bugs. In view of the much greater logical strength of dependent type theories, this situation is hard to understand.