Formalising mathematics in set theory

[resolution Mizar QED project set theory Hao Wang formalised mathematics Last week’s post mentioned the mechanisation of some major results of ZF set theory in proof assistants. In fact, the use of automated theorem provers with various forms of set theory goes back a long way. Two stronger set theories have attracted interest: von Neumann–Bernays–Gödel (NBG) and Tarski–Grothendieck (TG). All of this work was motivated by the goal of mechanising mathematics.

Early ambition on mechanising mathematics

The idea that all mathematical knowledge could be reduced to calculation has been around for centuries. It is associated with the 17th-century mathematician/philosopher Leibniz, who looked forward to a future where

when there are disputes among persons, we can simply say: Let us calculate, without further ado, and see who is right.

In the 20th century, some researchers expressed strikingly bold visions. Here is Hao Wang in 1958:

The original aim of the writer was to take mathematical textbooks such as Landau on the number system, Hardy-Wright on number theory, Hardy on the calculus, Veblen-Young on projective geometry, the volumes by Bourbaki, as outlines and to make the machine formalize all the proofs (fill in the gaps).1

What he actually accomplished was impressive enough. He implemented a proof procedure for first-order logic with equality, which he claimed to be complete. He demonstrated its power by proving nearly 400 of the purely logical theorems of Principia Mathematica. While thinking about that accomplishment, take a moment to examine the specifications of the computer used, an IBM 704. It’s notable that the first book mentioned by Wang was Landau’s Foundations of Analysis. As already described, that book would soon be formalised, using AUTOMATH. I presented here an example from “Hardy on the calculus” not long ago.

Here is Art Quaife in 1989:

$1000 personal computers with the computational power of the human brain should be available by year 2030. The time will come when such crushers as Riemann’s hypothesis and Goldbach’s conjecture will be fair game for automated reasoning programs. For those of us who arrange to stick around, endless fun awaits us in the automated development and eventual enrichment of the corpus of mathematics.2

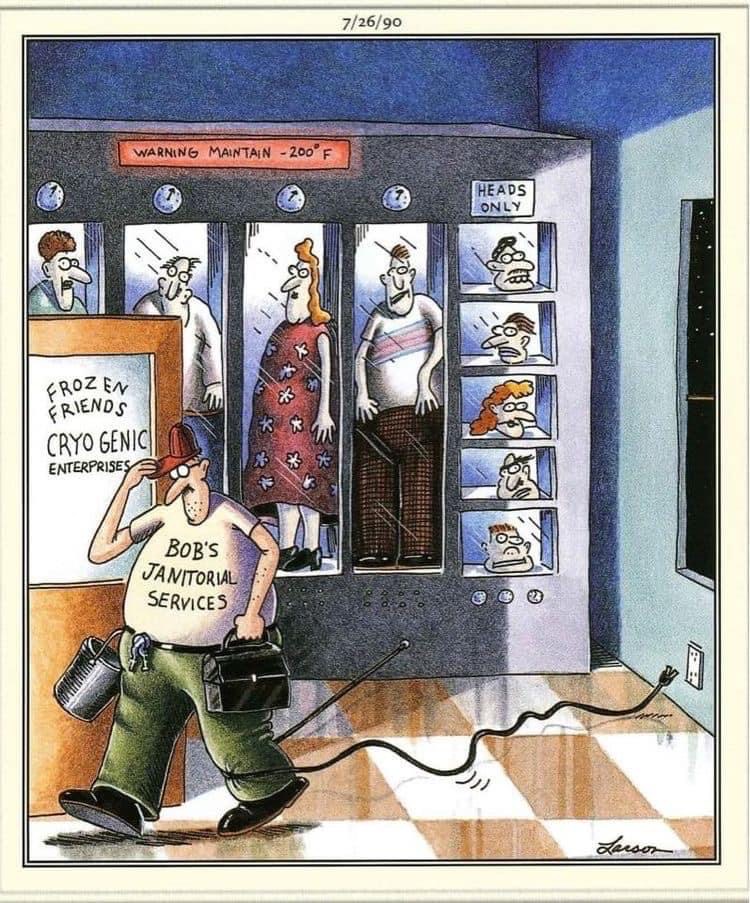

2030 isn’t far off, so this was a little ambitious (and we didn’t get HAL 9000 in 2001 either.) However, in the expression “arrange to stick around”, Quaife is referring to life extension technologies (a.k.a. putting your body in the freezer), so possibly we can add a couple of centuries to the deadline. With a complete proof procedure, a proof will definitely be found if one exists, but the time and space required could make it utterly infeasible. The freezer will thaw first. Gödel incompleteness could also spoil the party.

Quaife did achieve significant results however. He produced the first usable formalisation of axiomatic set theory in an automatic theorem prover. He used Otter, the leading resolution theorem prover of that era. Such provers are fully automatic, but in practice, somebody needs to lend a hand by suggesting lemmas to be proved in the correct order, and Quaife correctly described his proofs as semiautomatic. He proved Cantor’s theorem and a challenge that had been posed: that the composition of homomorphisms is a homomorphism.

The most ambitious proposal to emerge from this era (published in 1994) was the QED Manifesto (anonymous, but was said to be driven by Robert Boyer).

QED is the very tentative title of a project to build a computer system that effectively represents all important mathematical knowledge and techniques. The QED system will conform to the highest standards of mathematical rigor, including the use of strict formality in the internal representation of knowledge and the use of mechanical methods to check proofs of the correctness of all entries in the system.

So now the aim was to formalise all important mathematical knowledge.

NGB set theory

Quaife used von Neumann–Bernays–Gödel (NBG) set theory, as recommended back in 1986 by Boyer et al., because ZF set theory cannot be finitely axiomatized.

[ZF] cannot be input to a resolution-based theorem prover. Fortunately, the vNBG set theory has a finite axiomatization, and is in fact strictly stronger than ZF.3

From a syntactic point of view, the problem is that ZF involves terms that contain first-order formulas. NBG uses variables ranging over proper classes as surrogates for formulas, bringing them within the mathematical domain of discourse. (In ZF, classes are nothing but a convention for referring to collections––of all ordinals, say––that are too large to be sets.) NBG provides a selection of operations on these classes, including intersection, complementation and domain of a relation. From these it is possible to recover the effect of ZF’s separation and replacement axioms.

Unfortunately, rendering first-order formulas into this combinator language is difficult. Belinfante wrote code to automate the translation and performed a series of experiments, culminating in the the Schröder-Bernstein theorem.

TG set theory

In order to discuss Tarski–Grothendieck set theory, we need the notion of a universe. The terminology is unfortunate because “the universe” means everything there is. Here we are using it to refer to huge sets that are not everything there is, and nobody thought of calling them galaxies. So, staying informal, a ZF universe is a set that is a model of ZF set theory. Such a set cannot be proved to exist, by the second incompleteness theorem. But it’s natural to believe that such models exist, because otherwise (by the completeness theorem) ZF would be inconsistent, so why are you using it? Such a model could even be countable, by the Löwenheim–Skolem theorem: see Skolem’s Paradox. However, here we need large models, typically given by large cardinals.

TG set theory is ZF set theory plus Tarski’s axiom, which basically states that every set belongs to some Grothendieck universe. This axiom may sound unreasonably strong, since even the members of these universes imply the existence of further universes. However, set theorists are used to such assumptions. Through the gateway drug of an inaccessible cardinal (which guarantees the existence of one universe), set theorists have become addicted to a vast pharmacopoeia of unimaginably stronger assumptions. Tarski’s axiom turns out to be pretty tame compared with the others. Somehow, it also implies the axiom of choice.

The proof assistant Mizar

During the Cold War, those of us working in the West seldom noticed what was going on in the East not involving missiles and tanks, so the advocates of the QED Project were astonished to discover how much mathematics had already been formalised using a system that they had never heard of: Mizar, from the University of Białystok in Poland. It had been created in 1973 by Andrzej Trybulec. It offered a highly flexible language, based on Tarski–Grothendieck set theory, for mathematical concepts and proofs.

The Mizar language was designed to be readable by mathematicians while being strictly formal. Isabelle’s Isar language borrows heavily from Mizar. They are also pronounced similarly (if you are German).

The Mizar Mathematical Library accumulated contributions by a great many authors. Isabelle’s Archive of Formal Proofs is one of several modern-day imitators of the MML. There’s a Historical outline by Bancerek.

-

Hao Wang. Toward Mechanical Mathematics. IBM Journal of Research and Development 4:1 (1960), 15. ↩

-

Art Quaife. Automated Deduction in von Neumann–Bernays–Gödel Set Theory. Journal of Automated Reasoning 8:1 (1992), 119–120. ↩

-

Robert Boyer et al. Set theory in first-order logic: Clauses for Gödel’s axioms. Journal of Automated Reasoning 2:1 (1986), 288. ↩