Wittgenstein on natural science, mathematics and logic

[philosophy David Hilbert Kurt Gödel In a blog devoted to mathematics and logic, it’s hard to avoid Wittgenstein. Wittgenstein saw his main contributions being to the philosophy of mathematics and logic. I’m not sure that he understood either of them. But let’s begin with natural science, since it touches on topics relevant to this blog, such as the relationship between models and the real world. Natural science is another field where Wittgenstein indulged in his habit of obscurantism. Since I don’t know much about philosophy, perhaps I have no business criticising a famous philosopher. But I have the right to judge whether he is basing his reasoning on premises that are, if not correct, at least plausible.

Natural science

The Oxford Dictionary defines natural science as “the branch of knowledge that deals with the study of the physical world”. Such studies have been going on forever. Ancient peoples observed the heavens, watching the sun traverse the sky from east to west and the moon with its phases. They saw the stars fixed in their constellations within the firmament, which rotated as the night progressed, and the strange wandering stars (“planets”) that followed mysterious paths. They regarded the earth as stationary: a reasonable conclusion, trusting their sense of motion.

Over the centuries, astronomers made increasingly detailed observations, somehow learning to predict eclipses and the motions of the planets. The Antikythera mechanism, which dates to no later than 100 BCE, could perform these functions mechanically.

Many centuries later came the realisation, due to Copernicus, Giordano Bruno, and Galileo, that Earth, like the other planets, orbited the Sun. Observations by Tycho Brahe (working without a telescope) and Johannes Kepler led to Newton’s promulgation of the laws of motion and of gravity, mathematical formulas precisely fitting the observed motions of the planets (and still precise enough to take a spacecraft to Mars today).

We see different kinds of knowledge here:

- direct observations of specific events

- reasonable conclusions that were wrong, or only partly right, whatever that might mean

- adoption of models (the Copernican model preferred simply because of its greater elegance)

- refinement of models (Newton’s laws are a quantitative refinement of the Copernican model)

- rejection of models and even of observations

And we see lots of issues that trouble real philosophers of science. These include the difficulty of making accurate observations, of choosing among alternative models (what do we mean by elegance and why should a model be elegant?), of the role of predictions, how to deal with errors, and more fundamentally, the nature of reality and how to distinguish it from illusion. There is the problem of inferring natural laws from a finite number of observations: so-called inductive inferences, which could be disproved by further observations tomorrow. There is the question of why there should be any natural laws at all.

And then we have Wittgenstein, in his Tractatus:

The world is all that is the case

The totality of true propositions is the whole of natural science

He’s possibly trying to say something. Certainly, many highly intelligent people have tried to clothe this bare scaffold with meaning. If he has stimulated others to think original thoughts, that’s something. But on to mathematics.

Mathematics

It’s the easiest to quote from relevant entry of the Stanford Encyclopaedia of Philosophy:

The core idea of Wittgenstein’s formalism from 1929 (if not 1918) through 1944 is that mathematics is essentially syntactical, devoid of reference and semantics. The most obvious aspect of this view, which has been noted by numerous commentators who do not refer to Wittgenstein as a ‘formalist’ … is that, contra Platonism, the signs and propositions of a mathematical calculus do not refer to anything. … When we prove a theorem or decide a proposition, we operate in a purely formal, syntactical manner.

Although Wittgenstein’s view is particularly extreme, he’s not alone. One of the main proponents of formalism was Haskell B Curry, who had a point, because his own field of study — combinatorial logic — was indeed concerned with meaningless symbol strings. He might be compared to a ballerina declaring that work is nothing but dancing.

David Hilbert was also a proponent of formalism, in my opinion as a response to the numerous paradoxes that had rocked mathematics since the beginning of the 20th century. A hedgehog, confronted with mortal danger, rolls up into a ball, but Hilbert was no hedgehog. Having declared that Cantor had created paradise, he obviously did find meaning in mathematics. His formalism was a desperate attempt to salvage from the wreckage as much mathematics as possible. His chosen tool–Hilbert’s programme–was to reduce everything to a formal, provably consistent axiom system. But the very need for such a programme shows that mathematics had not been conducted formally before. How did Wittgenstein get the idea that it had?

It’s not too much to say that mathematics emerged from magic. Isaac Newton, called the greatest ever scientist, was also committed to alchemy and his version of the calculus, fluxions, relied on infinitesimals. Leonhard Euler also used infinitesimals and regularly bent the rules, e.g. manipulating infinite sums as if they were finite. He arrived at correct results not by obeying the rules of a formal system but by breaking them. There would be no rigorous (let alone formal) account of infinitesimals until the 1960s. Unsound and intuitive techniques dominated until the mid-nineteenth century, when a concentrated effort was undertaken by Cauchy and Weierstrass (getting rid of infinitesimals) and later Frege, Whitehead, Russell (the first serious effort at formalisation). The 20th century saw a concerted effort to purge intuition from mathematics. There is no need to purge something that never existed.

I have particular knowledge about the formalist philosphy: my field of research is the formalisation of mathematics. I’m aware of many instances were a mathematical proof was incorrect, yet the actual claim of the theorem still held. If proofs are mere calculations, then how do mathematicians perceive the truth of of claims for which they have no proof? If mathematics is meaningless, then why have so many mathematical conceptions aroused such visceral emotions?

The vivid language that mathematicians used to debate these points does not suggest meaninglessness. Contrast with something that’s really meaningless, like a Sudoku; try to imagine a Sudoku causing outrage or scandal.

But the really big problem with Wittgenstein’s calculational view is his apparent belief that mathematics consists entirely of proving things. First, you have to decide what to prove things about.

Creativity in mathematics

Prime numbers lie at the heart of almost every big question in mathematics. We don’t know who first identified the primes as interesting. But we know who introduced group theory: Évariste Galois. Somehow he conceived the concept of a group and recognised its importance. He identified the key concepts of group theory, notably normal subgroups, which play a role somewhat analogous to prime numbers. It is true, that Galois did all this in order to prove theorems and settle the question of which polynomial equations were solvable by radicals. But there was no calculation involved in arriving at the concept of a group. The same could be said of many other mathematical conceptions that we take for granted, such as measure theory or Latin squares.

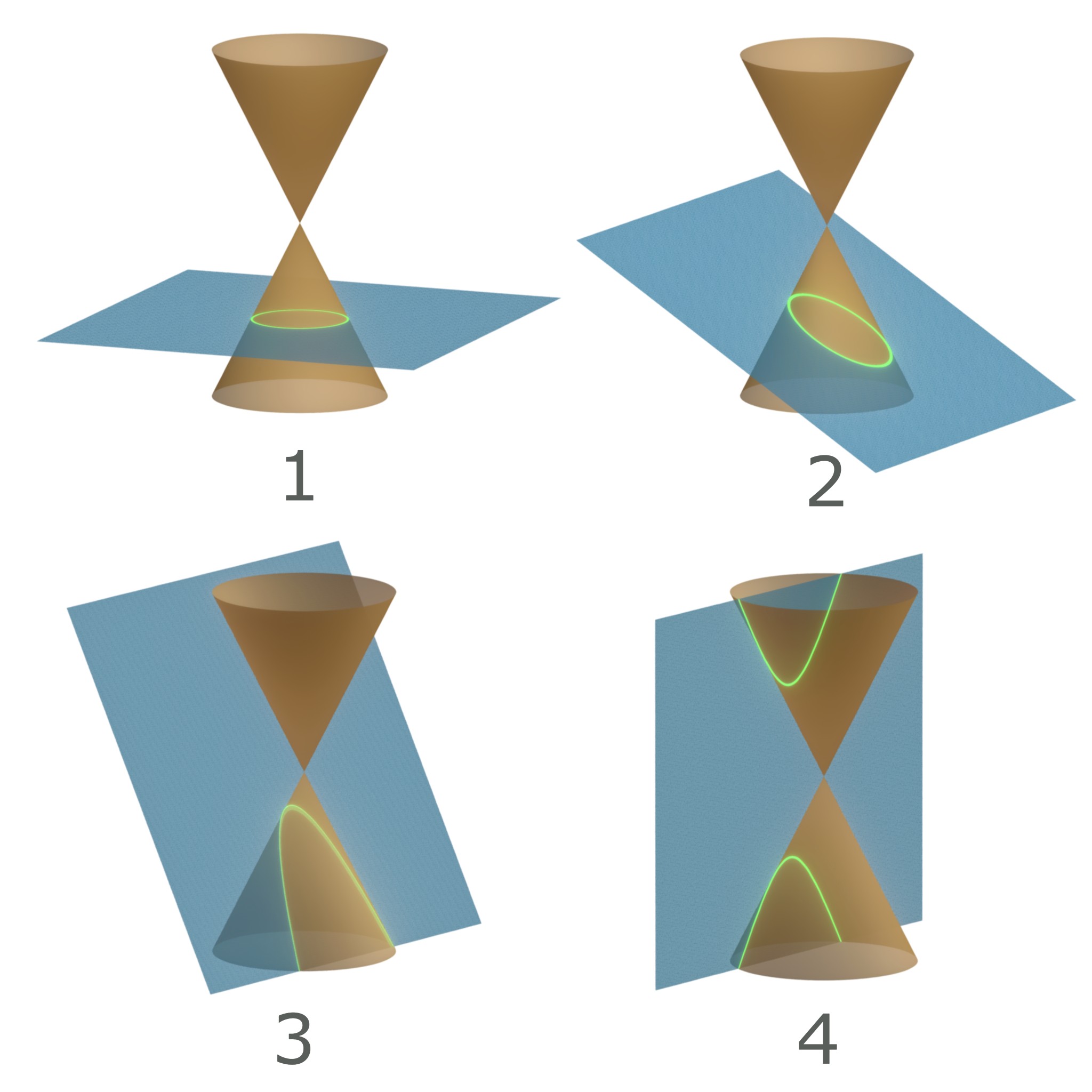

One of the most intriguing of these is conic sections. These were central to Greek geometry, and we might well wonder why. Certain kinds of mathematics were of obvious value to ancient people: arithmetic, for counting; plane geometry, for land surveying; three-dimensional geometry, for architecture. But what could possibly be the use of a cone?1

Somebody long ago fixated on cones and their sections: the circle, the ellipse, the parabola and the hyperbola. We don’t know why, but we know it wasn’t a calculation.

Turning to the modern day, one of the most inventive mathematicians was John Conway. His book On Numbers and Games begins with the definition of a new number system, as follows:

If L, R are any two sets of numbers, and no member of L is ≥ any member of R, then there is a number {L|R}. Al numbers are constructed in this way.

There is a fair bit more to this definition. Nevertheless, it does not directly conform to any pre-existing definitional principle. It took a genius, Conway, to write this definition. Others had to put in some effort to make it legitimate. Conway wasn’t following the rules but breaking them, inspired by earlier (and also doubted) work by Dedekind and Cantor.

Intuition in mathematics

It’s impossible to deny that formal calculation plays a role in mathematical proofs. But it plays much less of a role than some people imagine, as I discover every day when carrying out the process of formalising mathematics for real. Consider the statement “an eagle carried off a baby elephant”. We could decide its truth through elaborate calculations involving the strength of the eagle’s wings and claws and the efficiency of its respiratory system, along with the likely weight of the baby elephant. But that’s not how we do it. Similarly, mathematicians decide most mathematical questions using their intuition alone. They know whether a function is likely to be continuous, a polynomial is likely to have a real root, a set is likely to be countable. Most importantly, they surprisingly often know whether a deep theorem is likely to be true before undertaking the labour of proving it, and even if their proof is wrong. These are judgements, not calculations. Those of us who formalise mathematics are forced to come up with those omitted calculations and to fix the broken proofs.

Perversely, the very use of proof assistants seems to promote the idea that mathematics is inherently an exercise in formal calculation, despite the extreme difficulty of doing mathematics using such tools. Students say things like “mathematics is a formal system because mathematicians use set theory with its Zermelo–Fraenkel axioms.” Guys, 99% of the time, not even set theorists refer to those axioms. Their mode of working is as intuitive as anybody else’s. Other mathematicians are unlikely to be thinking about set theory at all.

While on the subject of intuition, let’s have Gödel describing Russell’s discovery of his famous paradox:

By analyzing the paradoxes to which Cantor’s set theory had led, [Russell] freed them from all mathematical technicalities, thus bringing to light the amazing fact that our logical intuitions (i.e., intuitions concerning such notions as: truth, concept, being, class, etc.) are self-contradictory.2

And this was no meaningless calculation, but a cataclysm that seemed to threaten mathematics itself.

Postscript

Wittgenstein served in World War I. His diaries and letters are powerful:

Life is a form of torture from which there is only temporary reprieve until one can be subjected to further torments. A terrible assortment of torments. An exhausting march, a cough-filled night, a company of drunks, a company of mean and stupid people. Do good and be happy about your virtue. I am sick and lead a bad life. God help me. I am a poor unlucky being. God deliver me and grant me peace! Amen.

Without doubt, he could write clearly and in plain language when he had something to say.

-

JensVyff, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons ↩

-

Kurt Gödel, Russell’s mathematical logic. In: P Benacerraf, H Putnam (eds), Philosophy of Mathematics: Selected Readings (CUP, 1984), 447-469 ↩